Stained Glass Stunners: A New Kind of Church Going

The City of London doesn’t quite conjure up images of a serene space. And it’s unlikely that the City will provoke within you thoughts of spacious halls flowing with tranquillity. Whether restaurant, train carriage or museum, we expect a definite throng; a swarm; an out-and-out mob of elbows and backpacks and bawling brats.

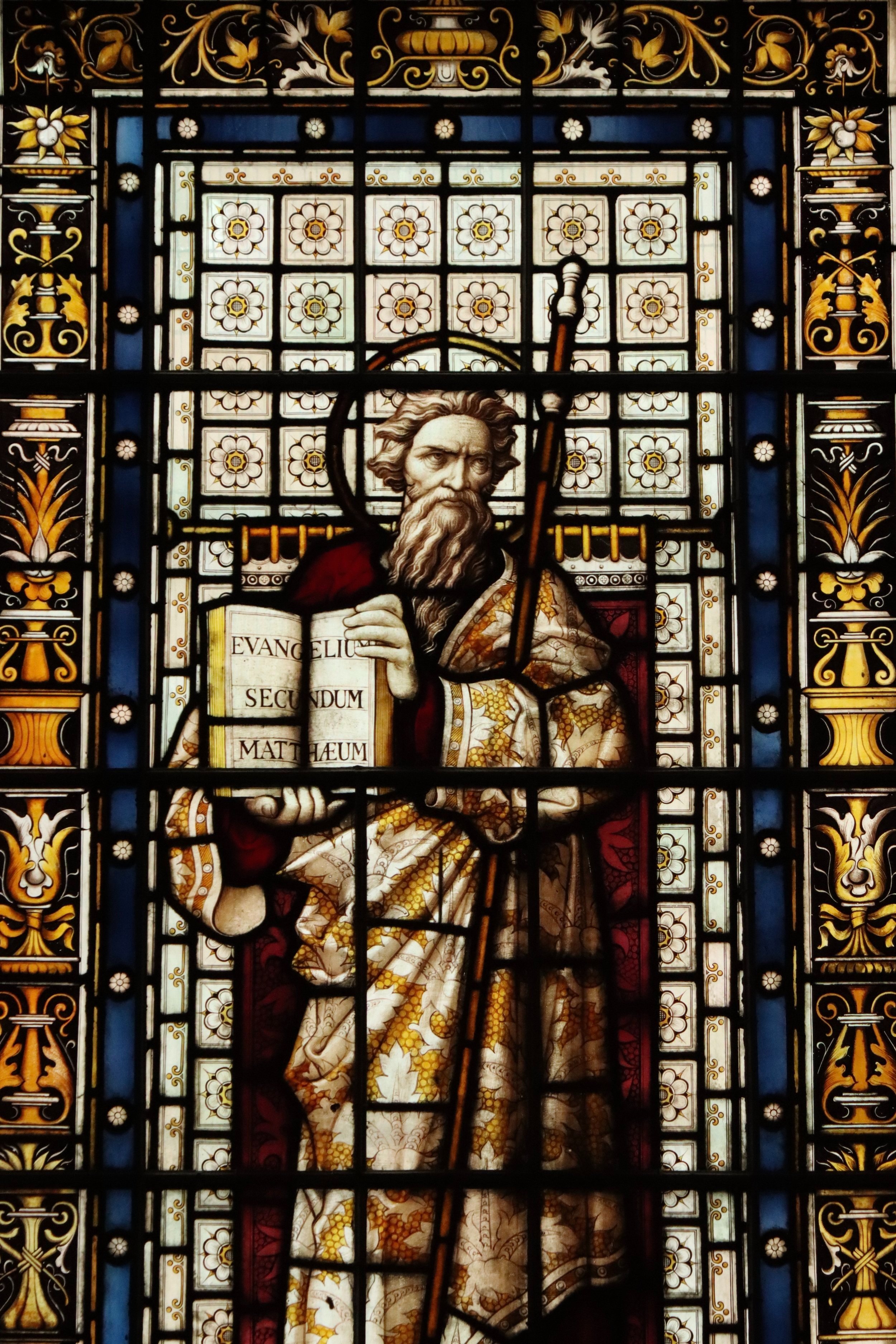

Yet search and ye shall find. The capital is covered in churches… or as I like to think of them, London’s much-overlooked stained glass galleries. While we may not worship as much as previous generations or view parishes as the integral community hubs they once were, there is another draw within these still and silent locales. For as you push the heavy, towering doors; tread lightly on the cold stone slabs; breathe the heady, archaic odour of incense, you will see – especially in the golden hours of the afternoon – a kaleidoscope of colours coating the aisles and warmly grazing the pillars. Stained glass windows are your new reason to visit houses of prayer.

London boasts an array of churches; survivors of war and victims of fire damage. In 1666, there were 101 churches, of which 80 perished in the Great Fire that September. Subsequently, 51 were restored. These days, shrinking flocks and an increasingly atheist society have resulted in many a house of God diversifying. Musical recitals are very common indeed, but there are even circus shows and boxing classes that have made use of the beautiful and capacious surroundings a church can offer.

The manufacturing process hasn’t changed much since the Middle Ages, when this art form was at the peak of its popularity. Molten glass is built up in a lump at one end of a blowpipe which is then blown into a cylinder. The cylinder is then cut, flattened and cooled. The pattern (called the ‘cartoon’) is then created. You can still study the craft today, either at university, by completing an apprenticeship, or, if you are deeply adventurous, The British Society of Master Glass Painters lists online courses whereby you can teach yourself, although to my mind blowing molten glass at home with no proper equipment has the same sort of risks as sky diving with no parachute.

In North West London, St Mary the Virgin stands on Primrose Hill and will be soon be celebrating the 150th anniversary of its opening for worship, in 1872. Apart from windows inserted behind the High Alter to replace glass lost in WWII, their glowing assortment of glass derives from the fine Victorian workshops of Clayton & Bell (one of the most prolific English workshops in the 19th and 20th centuries).

There are also delightful idiosyncrasies if you look closer. When one panel titled ‘Christ in The Carpenter’s workshop’, was being restored in 1950, the vicar insisted they had to include his cat. The feline appears incongruously perched at the feet of a Medieval personage. He is bulky, stripy and wears the expression of a condescending scholar. No matter, the vicar was smug as pie to have left his mark.

Over on the other side of London is Chelsea Old Church. Incessant bombing saw the obliteration of the Church’s mighty walls in 1941, though it has now been substantially restored and includes a memorial to a somewhat more illustrious patron saint than a vicar’s cat. The 1753 monument to Sir Hans Sloane is significant, since this gentleman’s collection shaped the British Museum.

These are the quaint and humble stories that one finds in the smaller churches of London. Of course, if you want grandiose or sprinkled with celebrity sex appeal you can always visit the David Hockney window in Westminster Abbey. The problem is that you’ll run into that unholy thronging crowd again. Much better stick to the quiet parishes, where colours carpet the floor and you can admire the different styles of glassworking in heavenly peace.